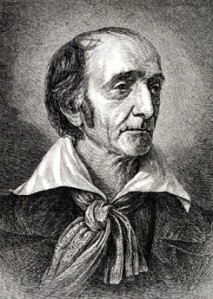

Today, October 7, Coast Survey celebrates the 245th anniversary of the birth of Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler, the Swiss immigrant whose plan to survey the U.S. coast was selected as the basis for the federal government’s first scientific foray, and who was to become the first superintendent of the U.S. Coast Survey. Hassler’s determination and uncompromising adherence to accuracy, precision, and scientific integrity during the decades-long struggle to establish the nation’s charting agency is a cornerstone of the NOAA of today.

Retired NOAA Captain Albert “Skip” Theberge, the noted NOAA historian, has written THE definitive paper on “The Hassler Legacy,” available online at the NOAA Library website. Theberge notes the formal biographical details, but then he goes beyond that, explaining how Hassler’s training and temperament contrasted with – and perhaps played into – the political machinations that resulted in a decades-long delay in the effort to create the young nation’s nautical charts.

On March 25, 1807 (after Congress passed “an act to provide for surveying the coasts of the United States”), Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin issued a notice to all interested scientific men in the United States, asking for plans to conduct the coastal survey. Hassler responded to Gallatin’s letter less than a week later, and his proposal for a trigonometrically-based survey was accepted in July. And then it gets really interesting. From Theberge’s article:

“However, no action was taken to begin the survey until 1811 because of the unsettled international political climate. Although Jefferson was among the most scientific of United States presidents, it was odd that he was instrumental in passing a law for the Survey of the Coast in early 1807; just three months before he had instituted an economic embargo against both England and France because of their depredations against American ships and seamen. This embargo resulted in the recall of over 20,000 American seamen on the high seas and effectively terminated the American merchant marine and international trade. The embargo continued until the end of his administration.”

“Jefferson’s successor, James Madison, reinstituted the Survey and sent Hassler to Great Britain in late 1811 to procure survey instruments. Because of continuing difficulties between the two nations, Madison declared war on Great Britain eight months after Hassler’s arrival in London.”

The inconvenience of being in England (and later, France) during the War of 1812 doesn’t come close to the inconvenience caused by “those penurious keepers of the public monies,” according to Theberge. Hassler went for long periods of not being paid, his purchase of survey instruments cost more than he was authorized (so he paid the difference out of his own pocket), and then the government refused to provide for his transportation home.

Florian Cajori, Hassler’s biographer, wrote:

“… A country of almost unlimited resources permitted this able scientist, who was giving his thoughts day after day to the advancement of science and to the glory of his adopted country, to return to America at his own expense and under financial embarrassment. The Government… permitted Hassler to be personally considerably poorer than he was before he undertook his mission to Europe.”

Despite the bad treatment, Hassler accepted the appointment as Superintendent of the Survey of the Coast on August 3, 1816, and he was soon on survey reconnaissance in New Jersey, accompanied by his son. In January 1817, after just a few months of work, the Treasury Secretary asked him to “state the probable time which will be required for the execution of this Survey.”

Theberge expounds nicely on the situation:

“Consider for a moment the utter lack of understanding by the national leaders of the nature of the task of charting the coast of the United States. There was a naivete, indicative of the state of scientific and engineering knowledge in the United States during the early nineteenth century, when Secretary Crawford asked a man, who had to construct his own measuring instruments, had no vessels, and had only his son for help, how long it would take to complete the Survey of the Coast.”

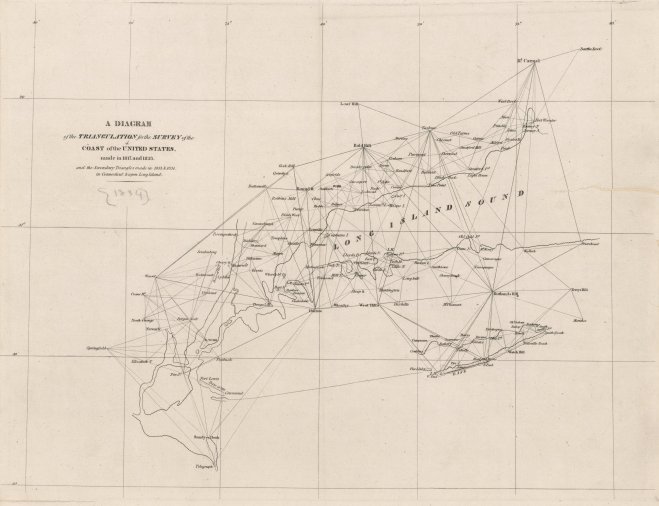

The next spring, the Survey of the Coast – and Hassler – took a major hit. Congress decided that only “persons belonging to the army or navy” should be employed for the survey. Hassler was out, and 15 years of scientific debate and survey ineptitude followed. It was during this time, cast off from the government, when Hassler laid out his vision. The task, he explained, was to construct a great triangulation network that would serve as the control for all nautical surveys as well as all national land surveys. In addition to the geodetic foundation for mapping the land and charting the coasts, Hassler envisioned the establishment of a national mapping organization.

Hassler, at age 62, was reappointed as superintendent on August 9, 1832, when the Survey was transferred back into civilian control within the Treasury Department. In 1834, the Survey of the Coast finally took its first ocean soundings. In 1836, the Survey of the Coast was renamed U.S. Coast Survey. Hassler served as superintendent until his death on November 20, 1843.

Ferdinand R. Hassler’s scientific achievements had laid the foundation for much of today’s NOAA.

I can no longer find Theberge’s online book on the Coast Survey at the URL you provide. Is it still available?