By Edward Owens

In a previous post, Edward shared his initial experience on board the Canadian Coast Guard vessel Louis S. St-Laurent as they traveled from Halifax, Canada, toward Tromsø, Norway. Today, he provides an update as well as a look at some of the features they found on the seafloor along the way.

It is a Sunday and our transit across the Atlantic on board Canadian Coast Guard vessel Louis S. St-Laurent is nearly complete. We’ll arrive in Tromsø, Norway, on Tuesday morning where we’ll rendezvous with a pilot boat to complete the final leg of our internationally coordinated hydrographic mission, as the latest contribution to the Galway Statement on Atlantic Ocean Cooperation.

Shortly after leaving Newfoundland, our communications capabilities dropped out and the science team began to coordinate the continual logging and processing of the hydrographic data. With a few minor tweaks, our deep-water EM122 multibeam and Knudsen 3260 sub-bottom systems were acquiring excellent data. Our route to Norway has been fairly direct, but modified in a few places of interest such as the mid-Atlantic Ridge zone, to junction existing multibeam data in the area and to develop curious features derived from satellite derived bathymetry. The weather has cooperated for us quite well and we have only experienced some patches of fog and a single 24 hour storm event. This event was more like a gail, however, where the winds were 50 to 55 knots and the seas about 6 to 8 meters, enough to put spray over the wheel house and for Neptune to assure us we were fast approaching the Arctic Circle crossing.

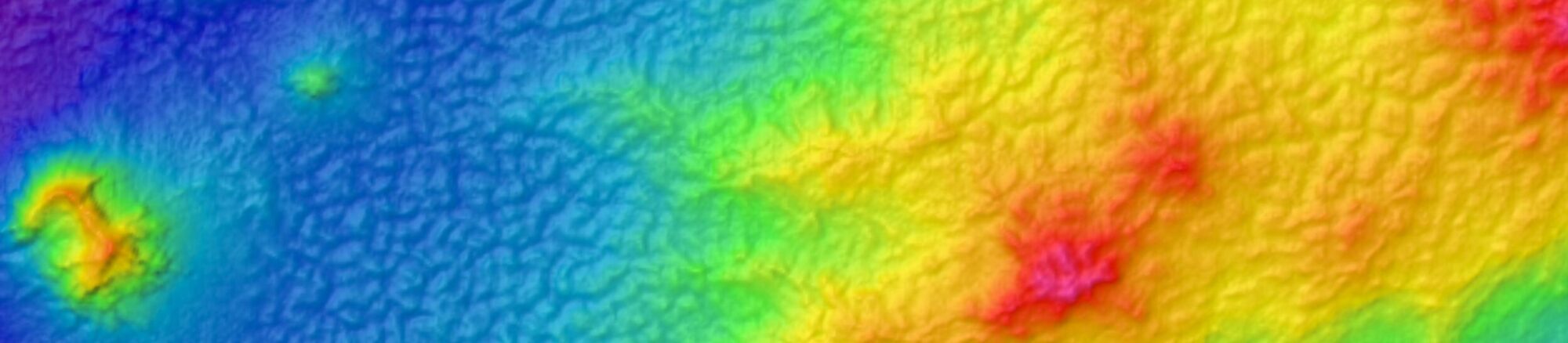

During our transit along and over the mid-Atlantic ridge the echosounders portrayed a dynamic seafloor of uneven terrain, gorges, trenches, ridges, and peaks. Of greatest interest to the team were a handful of small volcano-like seamounts ranging from 100 to 300 meters proud of the seabed and from 500 to 1500 meters across, all in over 2,000 meter depth range. The two most significant of these have been tentatively named the “Atlantic Heart” and the “Egg Cup”.

There is plenty of data to describe the area’s geological past. This section of seabed, and the ridge in general, forms part of the fault line that separates the European and North American tectonic plates and is being slowly formed by seafloor spreading. The two plates are moving apart by about 2 to 5 millimeters a year and as they do, molten magma from beneath the Earth’s crust seeps through the cracks from far beneath the surface which becomes lava and then cools and solidifies to form new seabed.

This process forms the ridge and all its visible scars, and it is in this area where we find the most dramatic seabed. These areas of uneven terrain are often the best places to find biogenic reefs and deep-water faunal communities. Many species of fish, coral, starfish, crab, and plenty of worms have been found living in association with these areas and aggregate to form nurseries and colonies. In this way, seabed mapping can begin to locate these communities which can then be managed effectively and conserved accordingly.

The Captain and crew are as fine as you could ever hope to sail with. There have been numerous social events and gatherings to get to know each other and share stories, along with the extremely important events surrounding the right of passage for all those, myself included, to graduate from a “pollywog” to a “shellback” if one can prove themselves worthy and of strong enough will to pass challenges and humiliation that Neptune demands in order to be accepted into his Northern realm of the Arctic Circle.

I will leave blank the details surrounding this rite of passage for all those who may experience this ceremonial affair. I will, however, leave you knowing I am now a loyal subject of this realm as dictated by my certificate from the Captain to alert all narwhals, walrus, and creatures of the sea that my sacrifices and suffering were sufficient to merit this honor.

Great job Ed.