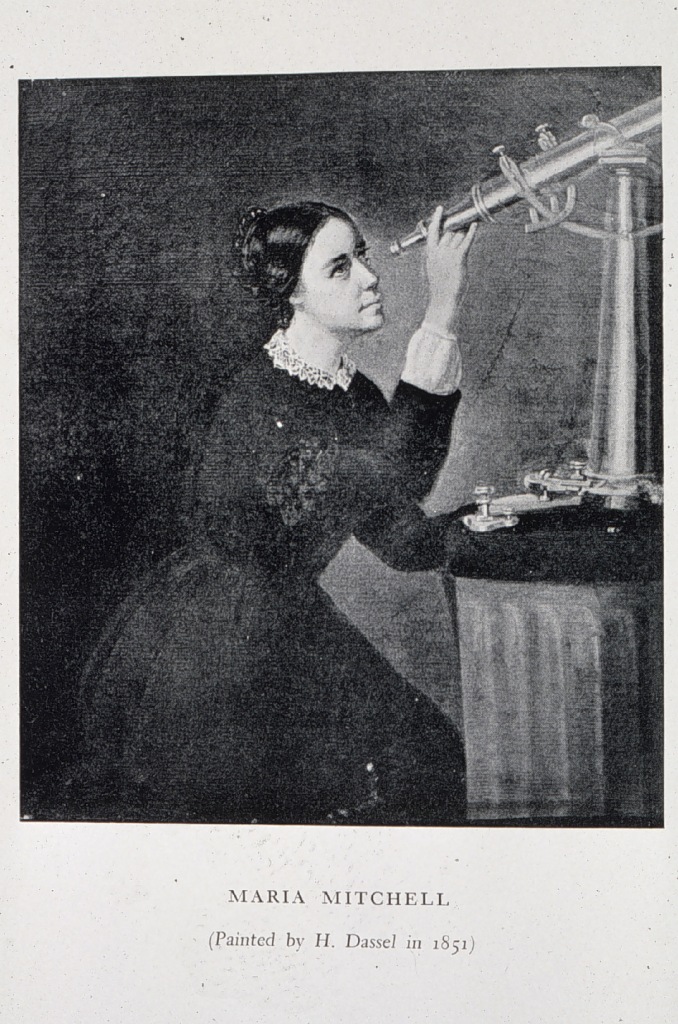

Among women trailblazers, there is one who may not be sufficiently recognized: Maria Mitchell, the first female professional employed by Coast Survey. March is Women’s History Month, so it is especially appropriate to introduce this extraordinary woman to the Coast Survey audience.

According to the National Women’s History Museum, Mitchell “probably was the first woman employed in a professional capacity by the federal government. Although women had been hired as cooks, laundresses, etc., her 1849 employment appears to be the first case of a woman earning an annual salary for work based on knowledge of an academic field.”

Actually, Coast Survey records indicate that she began her Coast Survey career in August 1845, when the agency hired her as an astronomic observer, based in Nantucket. Coast Survey Superintendent Alexander Dallas Bache asked Marie and her father, William Mitchell, to assist in observations associated with a project to establish a cardinal point for latitude and longitude for the United States and North America. Records indicate that Bache paid her $300 a year.

Retired NOAA Captain Albert “Skip” Theberge has woven Maria Mitchell’s story into his history of the U.S. Coast Survey.

“Bache’s progressive, although somewhat tight-fisted, views on managing personnel led to the Coast Survey being the first federal agency to hire women for professional work both within its ranks as permanent personnel and on a contract basis. The astronomer, Maria Mitchell of Nantucket, was the pioneer in this radical departure from custom,” Theberge writes.

Maria distinguished herself from the outset. On January 15, 1846, William Mitchell wrote to Bache, “I may say then that about all the moon culminations, since Loomis left us, have been taken (when visible) except through a part of one lunation, when Maria and myself were absent at Worcester. Maria alternates with me in these with a zeal (shall I also say skill?) very gratifying to an old man.”

On October 1, 1847, Maria used a telescope to discover a comet. “Her discovery was a major step in establishing her fame as the foremost nineteenth century woman scientist in the United States,” Theberge observes.

People today might find it strange to discover that there was actually an internal agency debate on whether to publicize Maria Mitchell’s association with the Coast Survey. Her own father wrote to Bache in 1848, expressing fear that some of the less enlightened members of Congress might note “…why, he employs a woman what a waste of money.”

Fortunately, Bache was not swayed by such concerns. He wrote a congratulatory note to “the lady astronomer in whose fame I take personal pride as having in some degree helped to foster the talent which has here developed… We congratulate the indefatigable comet-seeker on her success; is she not the first lady who has ever discovered a comet? The Coast Survey is proud of her connection with it…”

Phebe Kendall Mitchell, Maria Mitchell’s sister, picks up Maria’s history:

“In 1849 Miss Mitchell was asked by the late Admiral Davis [Charles Henry Davis], who had just taken charge of the American Nautical Almanac, to act as computer for that work, – a proposition to which she gladly assented, and for nineteen years she held that position in addition to her other duties… In this year, too, she was employed by Professor Bache, of the United States Coast Survey, in the work of an astronomical party at Mount Independence, Maine.” (Kendall, P.M. 1896. Maria Mitchell Life, Letters, and Journals. p. 24. Lee and Shepard Publishers, Boston.)

News and Updates