Coast Survey has been discovering and marking the locations of underwater dangers since our surveyors took the nation’s first official ocean soundings in 1834. We’ve used or developed all the technological advancements – lead lines, drag lines, single beam echo sounders, towed side scan sonars, and post-1990 multibeam echo sounders – and now we can point to a new major advancement for fast deployment and quick recovery. In February, Coast Survey’s Mobile Integrated Survey Team (MIST) used an autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) to locate a submerged buoy that was interfering with anchorages in the Chesapeake Bay.

“You and the crew of the HASSLER put us right where we needed to be!” said a confirmation email from the U.S. Coast Guard to NOAA Lt. Ryan Wartick, one of Coast Survey’s navigation managers. “Thanks for the great work!”

The problem began in early February, when an outbound tug struck and dragged a very large buoy and its anchor to an unknown location in the vicinity of Chesapeake Bay’s Thimble Shoal Channel. The U.S. Coast Guard closed adjacent anchorages because of the potential danger to navigation posed by the submerged buoy, affecting commercial vessel operations in the area.

On February 9, Lt. Wartick sat down with the U.S. Coast Guard, and other local and federal agencies, to arrange for Coast Survey mobilization in a collaborative effort to find the missing G “11” buoy. The Coast Guard asked Coast Survey to search Anchorage “A” on Friday, February 12, and provided a 45-foot vessel for our use.

Coast Survey’s MIST responders Robert Mowery and James Miller were able to pack up the AUV in Maryland and drive to USCG station on Naval Little Creek amphibious base, where they set up, calibrated, and hit the water on February 12 – and promptly located five potential targets, one of which looked especially promising.

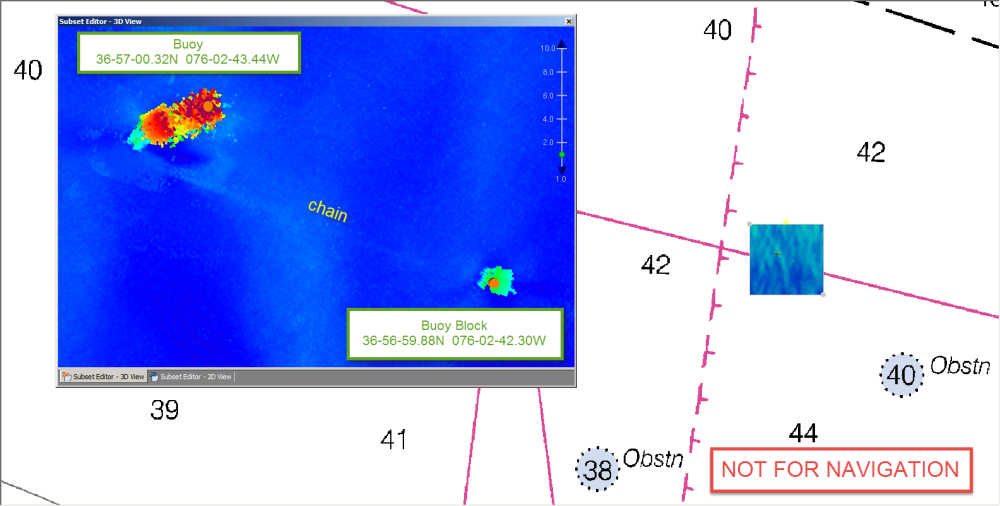

This side scan imagery, acquired by the Hydroid REMUS 100 AUV during the Coast Survey MIST initial search on February 12, shows the sunken buoy – although, at that time, the team was not 100% confident it was the buoy. The intensity of the sonar return and the dimensions of the target strongly supported their suspicion that this was the buoy, but the target was at nadir on the side scan profile, which introduces uncertainty in this type of system. They did, however, deem it the most likely among the five possible targets revealed by the AUV data.

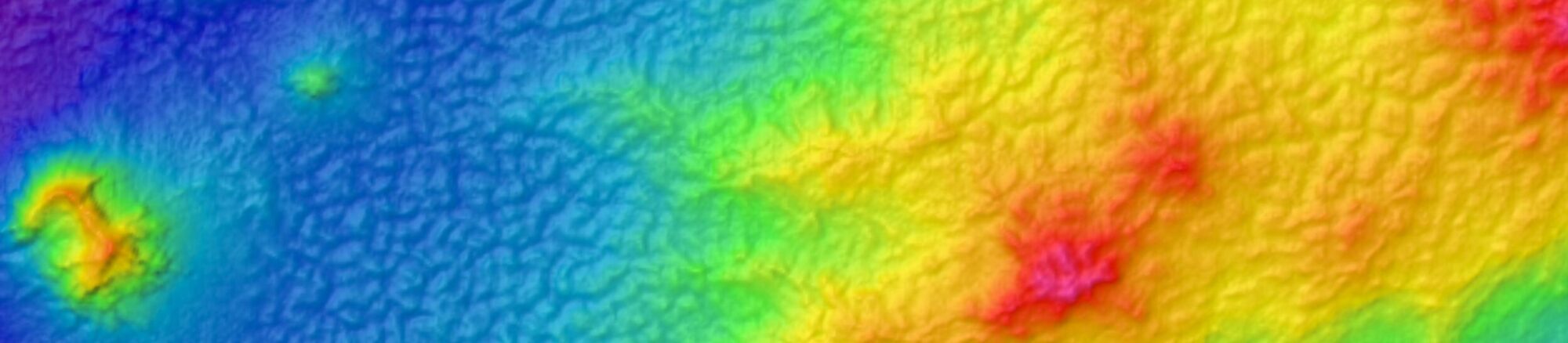

Fortunately, NOAA Ship Ferdinand Hassler was departing Norfolk on February 17, on their way to their survey project for the approaches to the Chesapeake, and so they made a slight adjustment in their route. The ship’s hydrographers used their multibeam echo sounders to check the targets, based on the MIST AUV data, and they confirmed that the top AUV target was indeed the buoy. The multibeam data also verified that none of the other search targets pose a danger to navigation or risk fouling an anchor for ships in the anchorage.

With the confirmation, the U.S. Coast Guard was able to remove the buoy and re-open the area for maritime traffic.

The Coast Survey Development Lab has been evaluating the use of autonomous underwater vehicles as tools for hydrographic surveying in support of NOAA’s nautical charting mission. The use of AUVs, in collaboration with NOAA’s manned survey fleet, could greatly increase survey efficiency. Additionally, as this response confirmed, their flexible deployment options make AUVs a valuable tool for marine incident response.

News and Updates