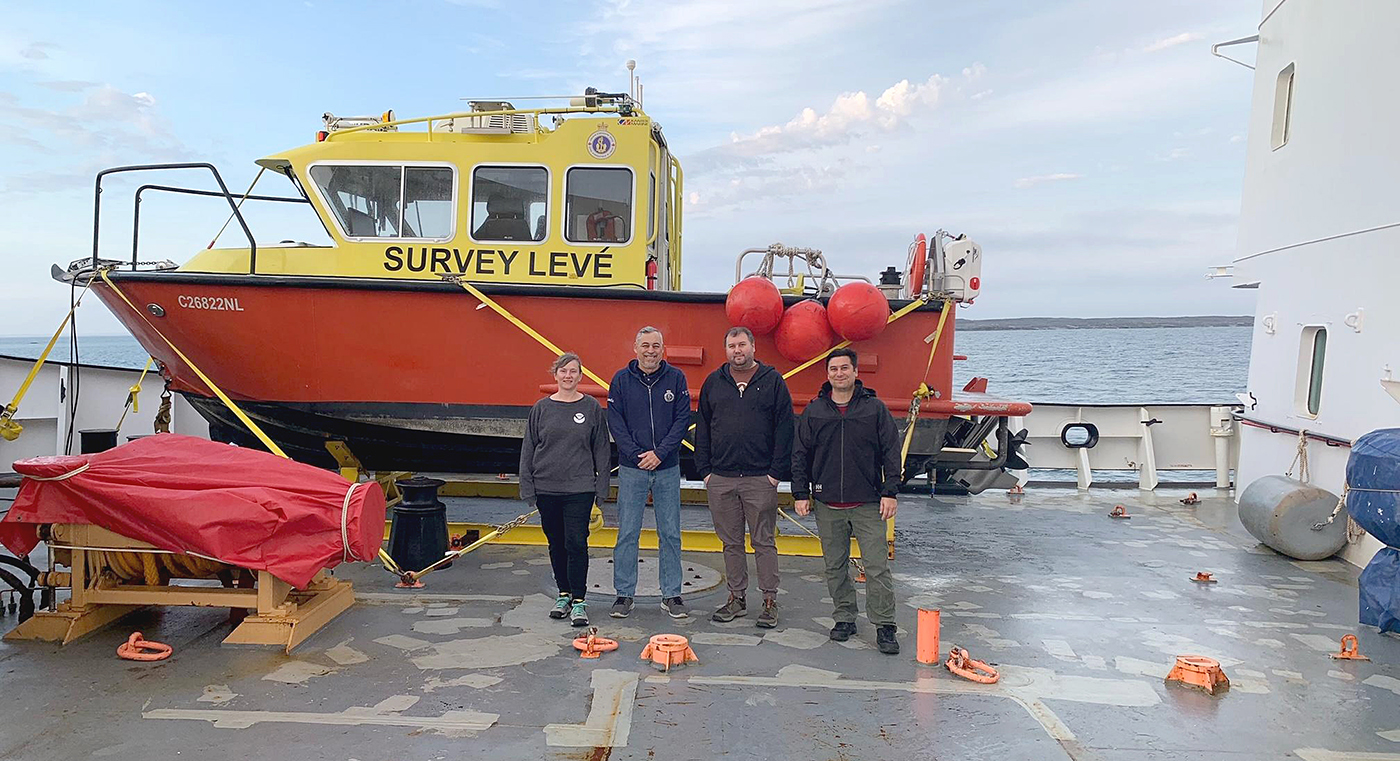

Annie Raymond, a member of one of NOAA’s navigation response teams, spent time in late summer aboard Canadian Coast Guard (CCG) icebreaker Henry Larsen in the Canadian Arctic with the Canadian Hydrographic Service (CHS). Her time aboard the ship was part of an exchange program designed as an opportunity for the Office of Coast Survey and CHS to gain exposure to each other’s field operations, particularly highlighting challenges for Arctic operations. Throughout the experience, she observed similarities and differences between Coast Survey and CHS data acquisitions and operations.

As a member of the navigation response teams, Annie is based out of Seattle, Washington and conducts hydrographic surveys to update the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) suite of nautical charts. Coast Survey’s mobile navigation response teams are strategically located around the country and remain on call to respond to emergencies to speed up the resumption of shipping after storms and to protect life and property from underwater dangers to navigation. The teams operate trailer-able survey launches equipped with multibeam and side scan sonar which help identify dangers to navigation after a storm.

Annie is no stranger to surveying icy waters. In November 2022, she and several other navigation response team members traveled aboard the U.S. Coast Guard heavy icebreaker Polar Star on its 25th Operation Deep Freeze in Antarctica. The Polar Star’s primary mission involves cutting a channel through the ice and clearing the way for supply vessels to reach McMurdo Station, Antarctica. While she was aboard, the Coast Survey team joined the regular mission in order to conduct a hydrographic survey of Winter Quarters Bay at McMurdo.

Surveying the Canadian Arctic

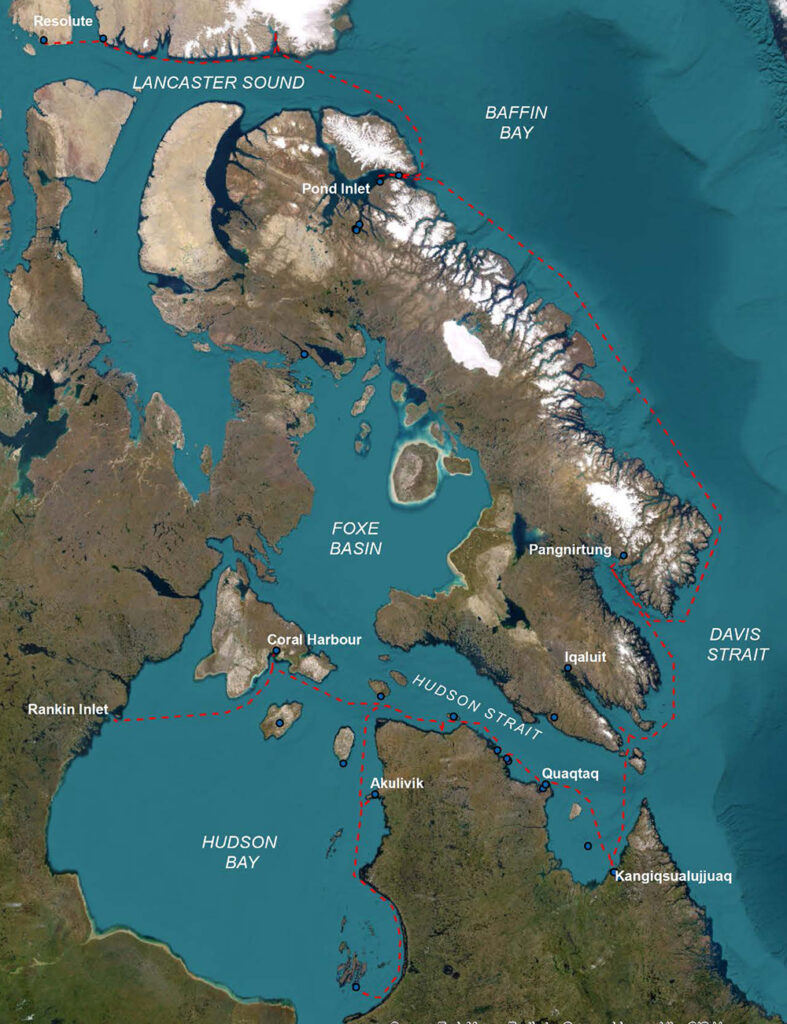

Annie joined the crew aboard the icebreaker from August 23 to September 21, 2023. It was an opportunity to gain exposure to the Canadian Hydrographic Service’s field operations, particularly highlighting challenges for arctic operations. US Arctic waters, including the north shores of Alaska, are notably different from the Canadian Arctic which contains the Arctic Archipelago. The numerous channels and passageways of the Arctic Archipelago make it considerably more navigationally challenging than the open waters of the US Arctic.

Generally speaking, polar surveying has a few aspects that set it apart from surveying in more temperate waters. In the Arctic, the cold can affect both humans and equipment. The field season is shortened due to available daylight and presence of sea ice. Best-laid survey plans can be impacted by quickly changing weather conditions or having to dodge icebergs. And, of course, there is the remoteness of the area and shear distance from assistance and services.

While aboard the Henry Larsen, Annie learned that the daily technical survey acquisition and processing operations for CHS are, not surprisingly, nearly identical to Coast Survey operations. Multibeam sonar equipment, acquisition and processing software packages, and acquisition steps employed are very similar between the two hydrographic offices. One notable difference in CHS’ acquisition and processing is the use of Fugro Marinestar® for positioning, which eliminates the need to post-process positional data (when fully operational). There are, however, more notable differences in organizational and operational structure.

Ship Operations

The Canadian Hydrographic Service does not own or operate their own large survey ships, as NOAA does, but rather ‘contracts’ time on other vessels on which they have installed sonars and survey launches. For surveys conducted via the Canadian Coast Guard vessels, this means that on a given cruise, only a fraction of the time might be dedicated to systematic hydrographic survey operations with the rest of the time given over to Coast Guard operations. Survey work is therefore limited to collecting data along the ships’ intended route or track. This differs from NOAA in that NOAA maintains survey ships specifically for hydrographic surveying operations and the surveys are systematically planned specifically for these vessels.

Canadian Coast Guard ships also notably operate on a 28-day crew rotation schedule. The entire crew from captain to deckhands rotate off and a new crew arrives every 28 days. The CHS team includes a hydrographer-in-charge, two watch standers (potentially more depending on the planned launch work), a data processor, and an electronics technician. Teams may overlap depending on the survey priorities and/or needs but mostly follow the crew rotation schedule. CHS provides its own launches and maintains all survey equipment installed, working with the ships electronic techs, deck and engineers as necessary. NOAA survey crews vary in number between survey platforms and units but generally don’t operate on an established rotation schedule which can contribute to fatigue, burnout, and high turnover.

Arctic Operations

The Canadian Hydrographic Service utilizes low impact shipping corridors based on automatic identification system data consisting of vessel traffic and regional input. Vessel traffic corridors in the Arctic are rapidly expanding with climate change and decreasing ice cover. Priority survey areas are established within those corridors. To the greatest extent possible, opportunistic track line surveys were aligned with both existing survey data and the shipping corridors.

The CHS is also actively engaging indigenous communities in the Arctic — both in the development and prioritization of the shipping corridors but also in creating a training program and providing custom designed data loggers to communities. The data loggers work with existing chart plotters and are a way to obtain additional ‘reconnaissance’ level data.

Not surprisingly, a lot of uncharted water exists in the Arctic. Data, where it does exist, is in various datums and sounding units — Canada has charts in feet and fathoms as well as meters. Fun fact; once upon a time, the CHS conducted systematic surveys using helicopters and a single beam sounder they would land and ping through the ice!

Final Takeaways

While many of the challenges impacting surveying in the Canadian Archipelago don’t directly translate to surveying in US arctic waters it’s encouraging to see all the similarities between CHS and Coast Survey from survey planning to technical survey acquisition and processing steps. It’s similarly interesting to note all the differences. Outside of the difference in ship structure and operations, CHS also internally maintains a training and development pathway for employees to cross-train as ‘multi-disciplinary hydrographers’ in tides, cartography, hydrography, and nautical publications. Regional offices each contain groups for tides, charting, and hydro with employees spending time working within each group. The design and potential benefits of such a model (particularly if paired with a set field work rotation schedule) in creating well rounded, cross-trained, interdisciplinary hydrographers may be the biggest takeaway.