By ACHST Simon Swart, Operations Officer Lt. Shelley Devereaux, and HST Adriana Varchetta

After six months of surveying in Alaska, NOAA Ship Fairweather was ready to point the bow south and set sail for San Francisco Bay. However, an unforeseen circumstance stymied the planned underway date. Although we eagerly anticipated the warmer waters of San Francisco Bay, this delay was well received by the hydrographers in the survey department and amongst the NOAA Corps officers. Our work had begun stacking up due to an extremely busy season, coupled with the fact that for most of us, this was our first time working on hydrographic project sheets. Therefore, we happily used this week of “down-time” to complete previous project sheets and plan for the upcoming survey. Those of us as sheet managers focused on cleaning multibeam data, processing backscatter mosaics, attributing features, conducting quality control checks, and writing descriptive reports. This process was greatly assisted with the help of augmenting physical scientists Pete Holmberg and Janet Hsiao. In the end, we were able to finish processing a number of sheets and reach a comfortable place on all the others. After a week of long hours, we were finally ready to toss lines and say “see you next year Alaska.”

The transit south began within Alaska’s Inside Passage, a calm sea route protected from the open ocean by island mountains. Sailing through the Inside Passage is always a crew favorite as it provides vastly new experiences each time. This trip, Fairweather achieved 17 knots through Race Passage. A pod of orca were spotted the next day – a rare sight with some of the veteran sailors aboard commenting that they had never seen orca in the passage. To an outsider, neither of these events may seem particularly significant, but to the crew they represent rare badges of honor that differentiate this season from others and provide a focal point for sea stories to be told in the years to come.

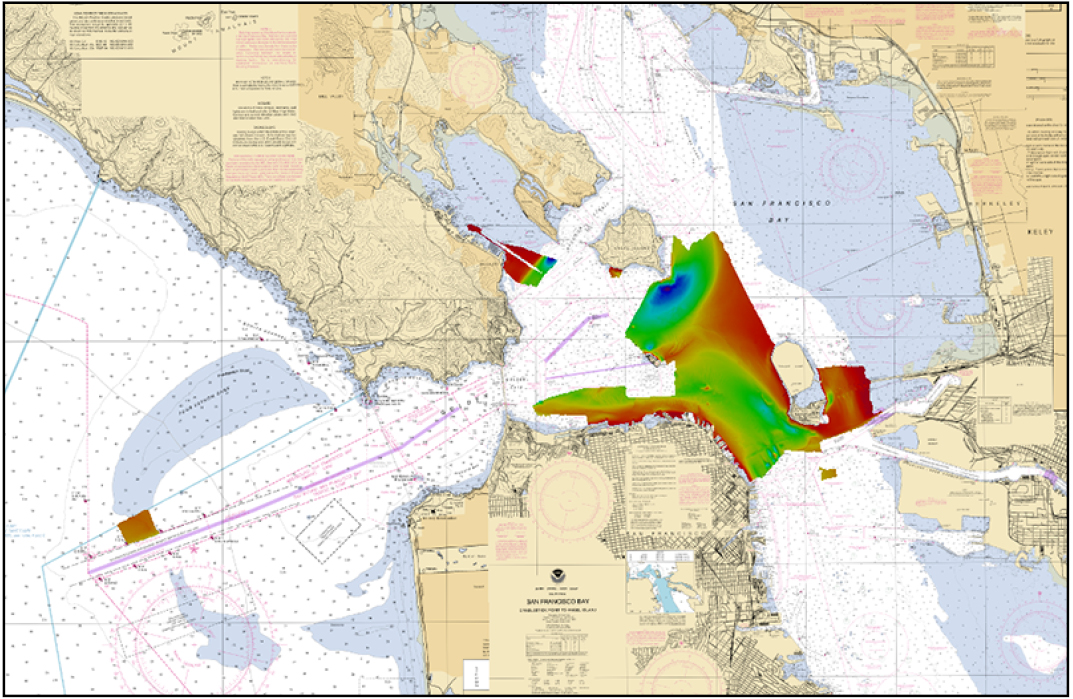

A few days later we arrived outside San Francisco Bay on what seemed to be a typically foggy day. As the ship transited under the Golden Gate Bridge, the fog lifted and our working grounds for the next week – from Alcatraz Island to Angel Island – were laid bare for us to take in. The crew was transfixed by the scenery as Fairweather transited to the anchorage point outside of Sausalito, California. We had not seen a town larger than 30,000 people for the previous six months and were mesmerized by the appearance and size of the manmade landscape before us.

The number of other vessels that Fairweather was suddenly dodging in the bay was an additional adjustment for our bridge teams – not a common problem in the remote regions of Alaska where seeing one or two other boats a day counts as busy. A San Francisco October brings out fisherman, kite boarders, sailing regattas, dredgers, pilot boats, 1,000-foot tankers, wind surfers, and even paddle boarders. Without a direct equivalent to street signs and traffic signals, the bridge team plans out a very specific route, makes passing arrangements with larger vessels, and keeps an eye on smaller traffic in case they’re unaware of the approaching ship.

Once safely anchored, smaller boats seem to take pleasure in passing close to the ship to wave hello and take some pictures, as it’s not every day they see a government research vessel. These mariners are very friendly and the crew is more than happy to oblige them by waving and smiling back. One interested member of the public flew a radio-controlled aircraft around the ship on multiple occasions to capture some aerial imagery of small boat deployments. You can imagine our surprise when, during our 0800 morning meeting on the fantail, we began to hear a buzzing noise overhead. Members of the crew stumbled upon this fans social media account and were impressed by his interest in hydrography and geography. He, in turn, was thrilled to touch base with surveyors as well.

This year, more than others, serves as a reminder that when survey equipment – and really anything in a marine environment – goes unused for a few weeks in port, some things don’t start right back up like you’d hope. This year the Fairweather endured several failed global navigation satellite system antennas. To achieve the high levels of positioning accuracy we are required to meet, each survey platform must have two antenna that receive signals and correctors from many different satellite constellations. If just one of the antenna is unable to receive a signal, the positioning systems ability to resolve its heading vector diminishes rapidly and the inaccuracies build quickly. The margin for error is not large. The upper limit of our heading accuracy threshold is 0.05 degree. When these antenna fail, we start seeing accuracy levels around 2.5 degrees, which results in poor data quality. The first day in the field, we had not one but two survey launches report these issues. Fairweather’s electronics technician pit crew spent time well into the late evening troubleshooting and swapping parts to have them ready to go the next day – a good lesson in always keeping spares handy. The last, still unresolved, part of the troubleshooting process is figuring out what exactly caused these failures as any platform downtime on the project hampers productivity. The leading theory at the moment is interfering signals from the plethora of other antenna affixed to the roof of the launch. This theory will be put to test once the manufacturer can run a full series of diagnostics on the failed units.

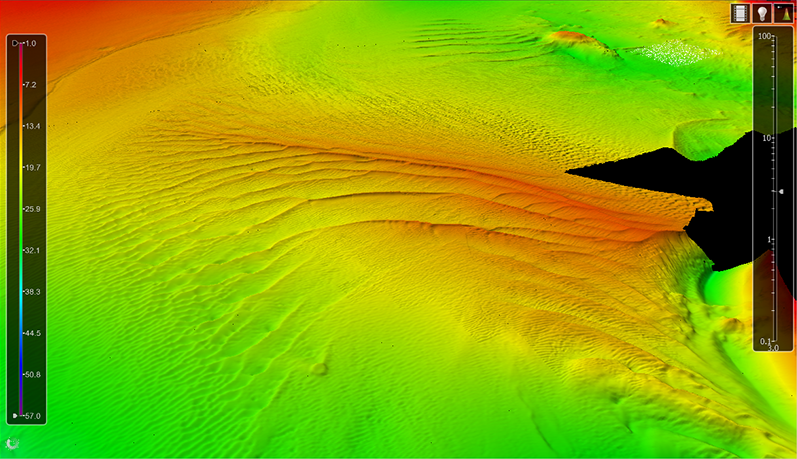

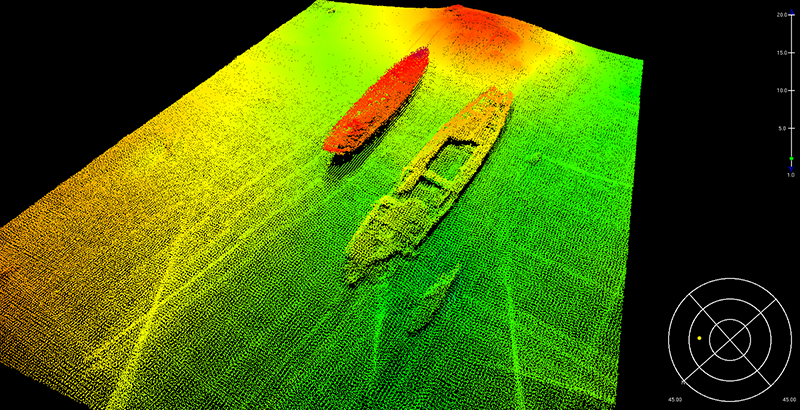

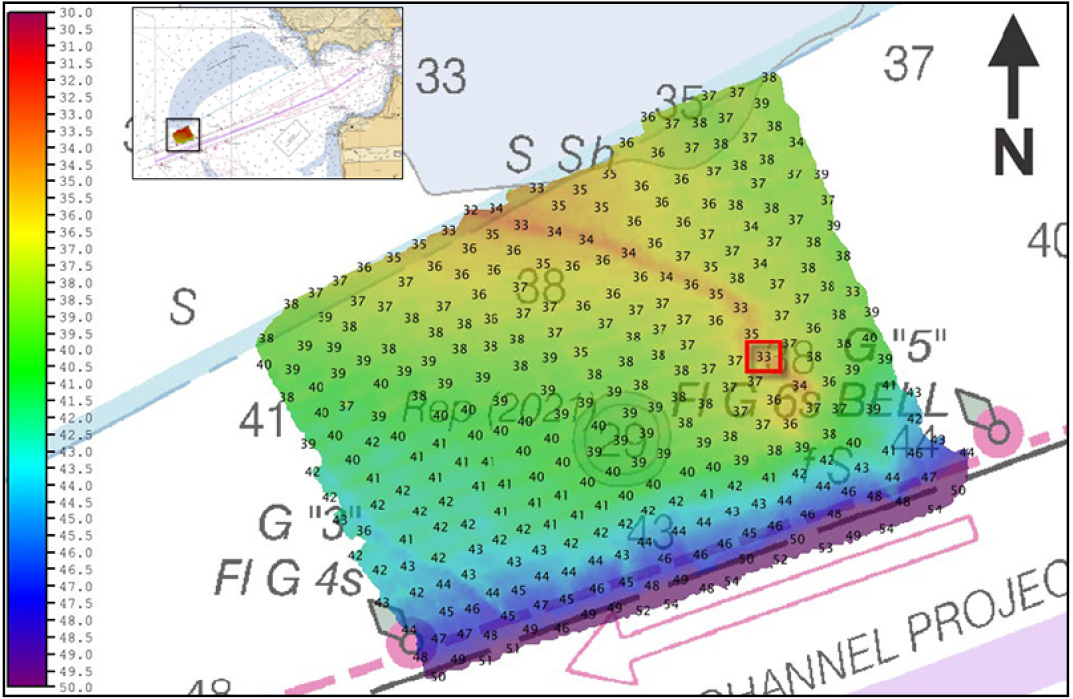

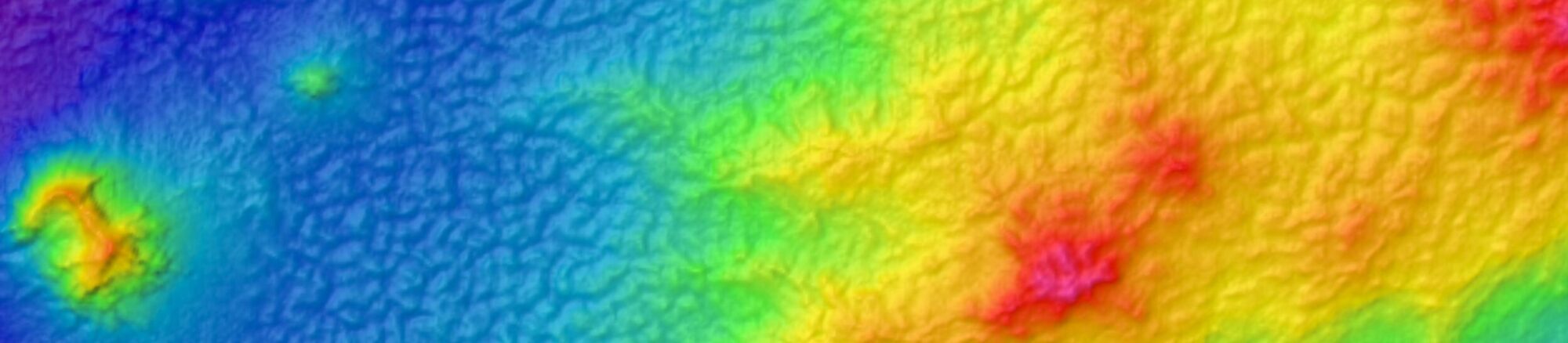

This project had a few survey nuances that are outside of Fairweather’s usual wheelhouse. We welcomed the change as it gives us a chance to expand our survey experiences and adapt to issues on the fly. Since San Francisco Bay is a critical port for commerce on the west coast, an object detection survey standard was selected for the project. Object detection surveys have a higher resolution surface, and stricter tolerances for missing data. In water up to 20 meters deep, we create a 0.5-meter grid instead of the usual 1-meter grid, and a 1-meter grid in depths from 20 to 40 meters. This might seem minor, but this change significantly impacts our acquisition practices. The first few days were a true experiment to make sure we were surveying slowly enough to achieve the necessary data density and meet object detection standards. These finer resolution surfaces are particularly important along the assigned channels, in between the piers of San Francisco, and over the numerous obstructions and wrecks in the Bay. While no new wrecks were discovered, it can still be exciting and eerie to see these developed with multibeam data.

We were also asked to investigate a reported shoal just outside San Francisco Main Ship Channel. This shoal was reported by another NOAA vessel in 2021, and was made a top priority to investigate for this project. While the shipping channel is maintained at a depth of 55 feet, the presence of a new shoal just outside of the buoys gives concern for any ships that regularly transit the area. Our survey launches peeked out beyond the Golden Gate Bridge to uncover the truth. While we didn’t find any evidence of the reported 29-foot sounding, we did find that Four Fathom Bank showed evidence of encroaching further south.

We were lucky enough to get a quick preview of Fairweather’s winter home in Alameda as we transited to Coast Guard Base Alameda Island for resupply and we look forward to finishing the work in the bay over the winter.

Hi

My wife used to take care of the paper charts at NOAA HQ in Silver Spring before the switchover to digital format by NOAA. She and a coworker, now retired, would do the inventory,order new charts when the supply was low, pull all requested charts and sent the charts to people who requested them including all US Gov entities, and also took care of the US Coastal Pilot Books also. Needless to say, she does miss working with the paper charts as she took care of them for over 25yrs.

Stay safe and following seas to you all